Unlocking a Bird’s-Eye View

I am always striving to do justice to the gorgeous and mysterious world we find ourselves in. We are surrounded by stunning beauty at every turn, and as a photographer and writer, I am always trying to bottle up that beauty to remember that moment and to share it with others. My work is always seeking to convey an echo of whatever feeling I experienced in a particular place and time. Perhaps it is a feeling of gratitude, wonder, or a welcome reminder that I am just a tiny, insignificant piece of this grand and wild place we call home.

Up until the last couple years, my efforts have been grounded. I was always envious of people with drones, but I stubbornly thought that I could do as much with my own two feet and a bit of grit and determination. I was terribly, and hopelessly, wrong.

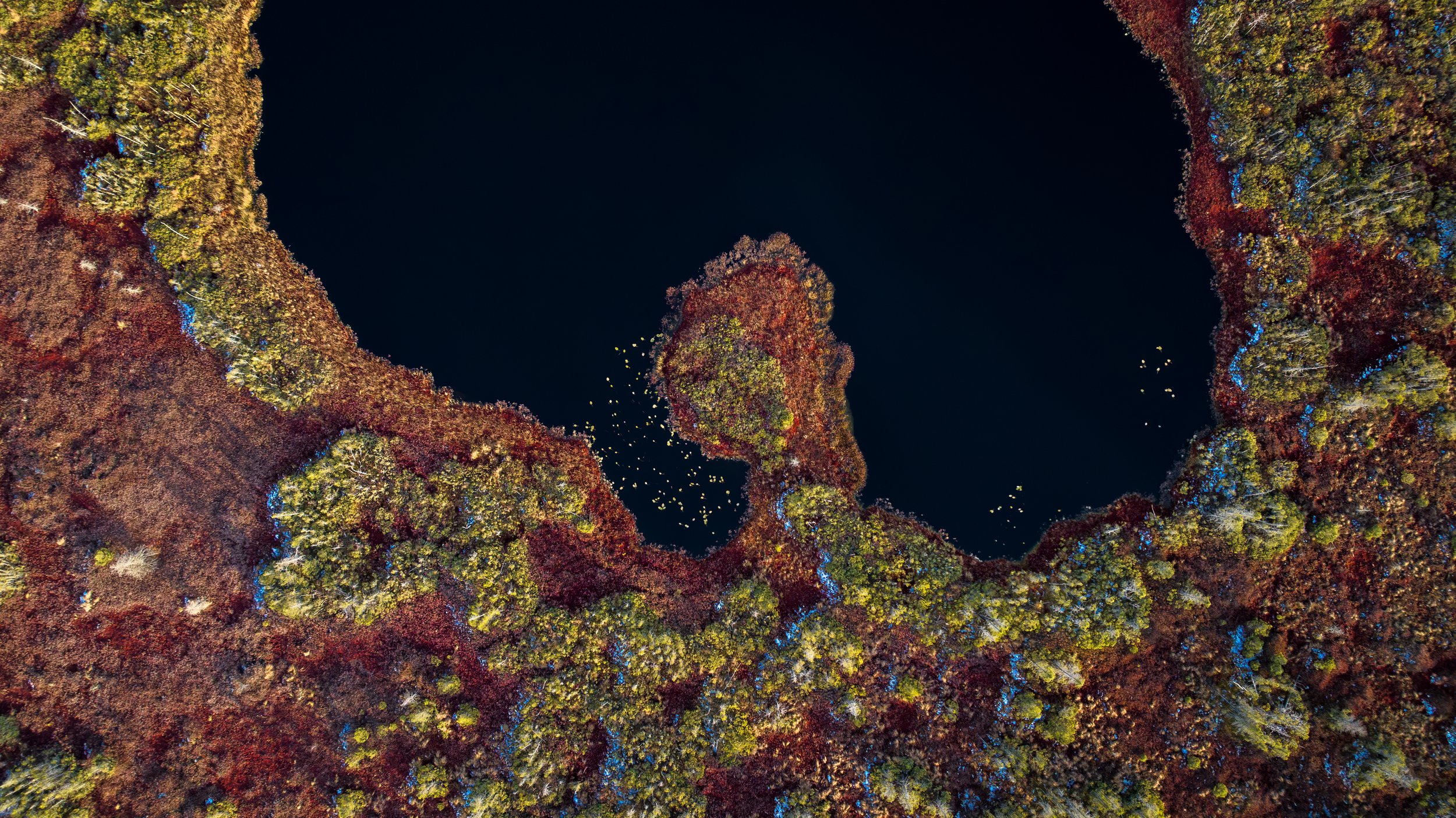

Aerial perspectives can be disorienting. Especially within environments that are unfamiliar to us, like peatlands. Click between the images above to see the same scene from two perspectives. The sphagnum moss reflects light differently from every angle, and the colors take on a different hue. The tannin-stained waters of the spring shift from a rich, deep blue, to a dark abyss.

In the last few years, I started working on the Northern Peatlands Project. These vast swaths of sphagnum moss peppered with black spruce and bog plants are as low and flat as you can get, and there is no surrounding topography to climb to get a bird’s-eye view. These ecosystems are also fragile and easy to disturb, and I didn’t want my traipsing to harm the very thing I am hoping to conserve.

To capture the mystery and awe of this landscape, and to communicate a feeling of wonder and awe to someone who has never been to a peatland before, I needed to get an aerial perspective. My land-based photography efforts simply weren’t doing the landscape justice. Short of climbing towering white pines on the edge of the peatland or hiring a pilot (both of which I’ve attempted to varying degrees of success), these bird’s-eye compositions were out of reach.

And so, in the name of our northern peatlands, I headed full-tilt into the world of drones.

Photographing peatlands from a nadir (down-facing) perspective feels a bit like a shared painting exercise, where the landscape is my collaborator. I move through different compositions, using swaths of brackish water as negative space, until I find something that evokes a feeling. Perhaps a sense of curiosity, wonder, or awe. Every time I experience this landscape, I am left feeling small and insignificant in the best way possible, in the same way that many describe feeling in the shadow of a towering mountain or waterfall.

When I flew a drone for the first time, I was stunned––and temporarily crippled––by the possibilities. Compositions I could only dream of were suddenly at my fingertips. I felt like I was stealing the power of flight from a bird of prey, stalking my next capture with the whining whir of my new-found wonder of flight.

Drone in hand, I turned my attention to the next step in the process––finding a location where I could legally operate.

The winding path to legal drone operations

I live and work in the heart of Adirondack Park, a patchwork of private and public land with some of the most stringent conservation regulations in the country. Most of the northern peatlands in Adirondack Park are located within New York State lands, and most of those are designated Wilderness. This designation prohibits the use of motorized equipment. Therefore, drones cannot be launched from these Wilderness areas. Occasionally Parks provide permission to drone pilots to operate in these areas, but the process is arduous and rarely successful for small business operators.

As I walk the trail onto a peninsula jutting into a vast peatland, I can make out glimpses of red, green, and gold sphagnum to my right, and snow-covered ground to my left. These glimpses become vast swaths of color when I see the landscape through the eyes of a flying camera.

I turned my attention to finding landowners who own land adjacent to peatlands, and worked to obtain permission to launch and operate a drone from their lands. Because airspace is regulated at the Federal level, I would be legally able to launch from private land and fly over Wilderness areas while following all FAA regulations.

The largest hurdle to this type of operation––launching where you have permission and flying over lands where you cannot touch ground––is maintaining visual line of sight. It is illegal to fly a drone beyond unaided, visual line of sight. Often forests grow right up to the edge of peatlands. Drone operators can expand their line of sight by hiring a team of Visual Observers who maintain eye-sight of the aircraft and communicate any obstacles to the pilot via radio, but these operations are expensive and challenging.

Therefore, I started to approach landowners who own the entire perimeter of the northern peatlands I was hoping to photograph. The first on my list—The Adirondack Chapter of The Nature Conservancy.

The Nature Conservancy’s Spring Pond Bog Preserve illuminated by late afternoon light on November 16, 2023.

Partners in conservation

The Nature Conservancy (TNC) owns and protects the entire perimeter of Spring Pond Bog, the second largest northern peatland in New York State. Their conservation efforts prevented developers from harvesting the peat for fuel, ensuring this habitat continues to cool our planet and provide safe haven to species that do not exist in any other environment. I’ve visited Spring Pond Bog alongside researcher Steve Langdon, and I knew this area would be ideal for aerial work. The raised peninsulas jutting into the peatland provide the perfect launching point and viewing platform for operations throughout the entire swath of sphagnum.

After pitching my project to TNC staff, donating a library of images to help TNC promote conservation of peatlands, acquiring a hefty liability insurance policy for drone operations, and engaging in a flurry of emails with the incredibly helpful and supportive team at the Adirondack Chapter of The Nature Conservancy, I was given permission to operate drones from Spring Pond Bog Preserve throughout spring, summer, and fall of 2023.

Footage from my first drone flight at Spring Pond Bog Preserve, July 2023.

Launching my drone for the first time, I was stunned speechless (and it wasn’t the droves of blackflies biting every inch of exposed skin that took my breath away). Everything I thought I knew about this area was turned on its head. I discovered bodies of water I didn’t know existed, colors of sphagnum I never imagined, and a plethora of wildlife trails cutting through the peatlands. I filled every memory card, drained every battery, and rushed back to my computer to edit my haul. I’ve never been so excited, so thrilled, by any photography project in my life. This felt like entering a new world, and I was only just beginning to discover these uncharted lands.

An outpouring of support

I have been floored and humbled by the outpouring of support for The Northern Peatlands Project. From my friends at TNC who provided permission to operate drones on their protected lands, to my inspiring colleagues at Talking Wings who invited me to contribute to the Listening to Water exhibition, to the team at Nikon for sending me equipment to help tell this story with bells and whistles I never imagined having access to––I am so grateful to the many peatland supporters who have come out of the woodwork to support this project. And of course, a huge thanks to the rapidly growing Secret Society of Peatland Enthusiasts who have signed up for The Northern Peatlands Project monthly publication.

A flight funded in part by the sale of Peatlands Postcards brought my perspective to new heights. Drone operations are limited to 400 feet above ground. Here, we are flying more than triple that height to get a full view of this extensive peatland. Nikon provided me with their Z8 camera to test the capabilities of one of their most powerful machines, upgrading my equipment from the sunsetting Z6 and opening up new possibilities for the Northern Peatlands Project.

Only just beginning…

This is the start of a wondrous journey. We’re going to learn about peatlands together, through the seasons and across the years. Thank you for being a part of this community, and supporting this work. And as always, if you have questions, ideas for a future article, or general thoughts about peat, please get in touch and spread the word.

Let’s see if we can make the Secret Society of Peatland Enthusiasts not-so-secret anymore.

Peatland Wonders: Quick Facts

For all those article skimmers out there, this one’s for you! Here are a few pretty pictures and quick facts to keep you coming back for more…

A close look at sphagnum moss reveals a feathery, water-logged structure. These water-loving plants can soak up more than eight times their weight in water, and they were used to dress wounds in WWI during a cotton shortage. Not only are they great at absorbing moisture, but they also have antiseptic properties.

The sickly sweet smell of nectar draws ants, flies, bees, slugs and snails into cavernous tubes. They use the hairs along the surface of the leaf to aid their descent. Those that drink from the basin will not return—the nectar is laced with toxins.

The downward-facing hairs on the inside cup of the pitcher plant form a field of impassable spikes. Drugged prey attempt to climb out, but slide back down, eventually falling into a pool of digestive acids and enzymes. The pitcher plant feasts on its prey.

Welcome to the mysterious world of carnivorous plants, many of which rely exclusively on bog and peatland habitat.

Aptly named given I found this dragonfly in November, an Autumn Meadowhawk rests on my hand on a sunny fall day. Even in late fall, I was being eaten alive by blackflies who thrive in the wet environs of peatlands. I was grateful to this veritable Helicopter of the Insect World for doing its part to control the blackfly population.